What Computer Control Misses and how Natural Intelligence can Help

This blog post serves a dual purpose: to organize my thoughts and to disseminate my ideas to a broader audience (that hopefully provides feedback). Concurrently, I am in the pursuit of a formulating a research question for my doctoral research. I have amassed a reservoir of potential topics - Yet, the crystallization of a precise research question eludes me. My intention in writing this post is to catalyze the refinement of my thoughts and ultimately pinpoint an area of research that ignites my fervor.

Computer Control

The ability to control computers through natural language (NL) instructions harbors enormous potential, as it allows for the automation of various tasks. This blog post delves into the intricacies of agents, which execute actions on computers based on NL commands, shedding light on their strengths and limitations.

We define the task of computer control as follows: The agent operates within a computer environment, such as a personal computer, notebook, or smartphone. We denote the state space of the computer environment as \(\mathcal{S}\), with a single state of this environment at time \(t\) represented as \(s_t \in \mathcal{S}\). Typically, the agent only observes a partial aspect of this state, denoted as \(o_t \in \mathcal{O}\), where \(\mathcal{O}\) is the observation space. This partial observation, \(o_t\), may lack certain details present in \(s_t\). For instance, while \(s_t\) could represent a personal computer with multiple running processes, the agent’s observation \(o_t\) might be limited to a pixel-based screenshot captured from the user interface.

The agent can perform various actions denoted as \(a_t \in \mathcal{A}\), within the action space \(\mathcal{A}\). The action space might include a low-level interface, such as the computer’s keyboard or mouse, or a higher-level interface, such as an API that can be called programmatically and then performs actions within the environment. Typically, a stochastic policy \(\pi\) determines the action to take based on the agent’s observation and a given natural language instruction denoted as \(i\):

\begin{equation} a_t \sim \pi(\cdot | o_t, i) \end{equation}

Note that we do not use a subscript \(t\) for the instruction \(i\), as it is typically provided at the beginning of a trajectory sequence \(\tau = (o_0,a_0, o_1, a_1, ...)\). Consequently, after receiving an instruction \(i\), such as “Open the calculator app,” the agent captures a representation of the system’s state \(o_0\) (e.g., a screenshot) and then samples and executes an action \(a_0 \sim \pi (\cdot \mid o_0, i)\) (e.g., clicking on a symbol). This process of observing and executing actions iteratively repeats until a stop criterion is met.

Existing Approaches

This blogpost does not aim to provide an exhaustive overview of existing approaches in computer control. Nonetheless, it is essential to highlight the two primary paradigms that have been employed to tackle this task: Reinforcement learning (RL) and large language models (LLMs).

Reinforcement learning methodologies typically operate within two types of observation spaces \(\mathcal{O}\): These spaces consist of either raw pixel data representing the user interface, a more abstract representation such as the Document Object Model (DOM) in the context of web browsers, or a combination of both. The action space \(\mathcal{A}\) is commonly defined by actions such as mouse movements, clicks, or keyboard inputs. The agent’s policy \(\pi\) is usually acquired through iterative interaction with the environment, during which the agent receives feedback in the form of a reward signal based on the efficacy of its actions. This reward signal is often sparse and delayed, presenting a significant challenge in the learning process.

In contrast, LLMs harness the capabilities of natural language processing (NLP) to comprehend and carry out instructions conveyed in natural language. These models can either directly process textual descriptions of the user interface or utilize an additional model to convert pixel-level observations into textual representations. The set of actions, denoted as \(\mathcal{A}\), is typically delineated by high-level commands such as XML patterns or API calls, specifying how to engage with the environment. State-of-the-art (SOTA) LLMs surpass reinforcement learning (RL) agents in terms of both sample efficiency and adaptability to novel environments. This superiority stems from their pretraining on extensive corpora, endowing them with certain “reasoning” abilities that enable the formulation of step-by-step plans for interacting with the environment.

My Bitter Lesson: Am I too Slow?

While writing this post, I experienced a surge of excitement as I formulated a compelling research question along with its accompanying sub-questions and some ideas how to tackle them. I couldn’t help but envision this endeavor evolving into a series of impactful papers, potentially shaping the trajectory of my PhD journey. However, it took me, due to vacation and other obligations, about two weeks to write this post. It was during this time that I stumbled upon a published paper that not only mirrored my idea but had already implemented it. The realization was a humbling reminder of the rapid pace at which this field of “agents for computer control” evolves (with an average of ~10 publications per month).

Acknowledging the reality of this swift-moving landscape, it became evident that speed alone would not suffice in navigating the intricacies of academic research, especially for an individual researcher. As I reflected on this experience, it underscored the importance of not only identifying the state of the art but also pinpointing areas that offer less competition—a niche where one can make a meaningful and enduring contribution without the looming threat of rapid invalidation.

Ultimate Goal

On personal computers, the majority of applications are navigated by users through a pixel-based UIs (as \(\mathcal{O}\)), alongside input devices such as keyboards and mice (\(\mathcal{A}\)). The goal of this research is the development of an autonomous agent proficient in comprehending natural language instructions and effectively controlling the computer system akin to human interaction. Specifically, the agent should utilize the pixel-level screen as its observation space \(\mathcal{O}\) and the keyboard and mouse as its action space \(\mathcal{A}\). Using these interfaces, the agent should be able to execute a wide range of tasks on various applications and not be limited to a few apps that provide specific interfaces (such as APIs, HTML source code, etc.). This agent should possess the capability to interpret natural language instructions and execute tasks delineated by human operators. Although this endeavor is more complex compared to using higher-level interfaces, it offers unparalleled versatility with potential applicability across diverse computing applications.

Current research focuses especially on creating policies \(\pi\) that allows agents to act on limited observation spaces \(\mathcal{O}\) such as HTML from web browsers, the view hierarchy from Android, etc. Hence, SOTA models typically require textual descriptions of the user interface, which are for most applications not available. Other approaches, claiming that they can work with pixel-based observations, are often pre-trained on screenshot-HTML pairs, allowing to translate the pixel-based observation into a textual representation of the user interface. However, these applications typically do not scale well as the pre-training focuses on specific domains such as we browsers and does not consider, for example, older CRM systems. Approaches that directly work with pixel-based observations are still in their infancy and perform surprisingly bad.

I argue that the missing ingredient for the success of computer control agents is the ability to understand UI elements and that it is key to derive actionable representations.

“Being able to derive actionable representations from pixel-based UI observations in a unsupervised manner is fundamental for controlling computers.”

– Me

Having actionable representation allows a model to understand the consequences of actions, i.e., it can predict the next state of the environment given an action. Such representations are fundamental for planning and reasoning, combining these with existing models would allow to act on various applications.

Research Question

Based on these insights and the current state of the art, I believe that the following questions will be answered by others:

- How to use LLMs for computer control?

- How to use RL for computer control?

- How to access the UI screen using LLMs?

- How to use mouse and keyboard using LLMs?

- How to find elements on UI screens and map them to instructions?

Maybe, instead of LLMs, novel research will use hybrid vision-language models to control computers. However, the principle remains the same.

I believe that others will not focus on the following question:

- How to control various unknown applications without expert demonstrations? (Most research focuses on specific applications such as web browsers, Android applications, or similar.)

Furthermore, I think that classic RL leveraging a reward cannot scale well as for most applications, the reward is not available. Hence, it is too sample-inefficient to be trained from scratch using pixel-based observations. LLMs, on the other hand, provide reasoning capabilities that are sufficient for some applications but are not yet able to generalize to non-mainstream applications (e.g., companies’ internal application, old CRM systems, etc.). Thus, to advance computer control for various applications, I believe that an interplay between discovering and understanding screen elements and reasoning is necessary. This interplay must be self-supervised (or at least very sample efficient), as expert demonstrations are not available for various applications.

Based on this insights, I identify two main research questions:

- How can we derive actionable representations from pixel-based UI observations in an unsupervised manner to enable agents to control computers across diverse applications?

- How can we implement a hierarchical planning based on a high-level instruction and multiple low-level actions?

The first question deals with the problem of understanding the UI screen and the consequences of actions. These are considered rather understanding atomic elements (e.g., clicking button “xy” creates a new document). The second question deals with the problem of breaking down a high-level instruction into multiple atomic elements (e.g. to write a letter: Open a new document, select font, …)

These questions include the following sub-questions:

- Actionable representations

- How to identify actionable objects (unsupervised)? E.g., “where can I click and type?”

- How to learn the consequences of actions (unsupervised)? E.g., “what happens if I click here?”

- How to represent actionable objects in a way that is useful for planning and reasoning? E.g., “how to map a learned world model to instructions and reasoning?”

- Hierarchical planning

- How to break down a high-level instruction into multiple atomic elements?

- How to plan and reason based on a high-level instruction and multiple low-level actions?

- How to align language instructions with actions?

UIs pose the challenges that

- agents can observe the screen to learn but typically no expert instruction is provided -> the agent has to come up with an interpretation what the user is doing

- UIs are complex and diverse -> the agent has to be able to generalize to various applications

- UIs contain multiple windows, and windows contain multiple sub-windows. Typically, the focus is only on one sub-window

- UIs scale with the screen size and window sizes can be adjusted

- UIs can change due to hovering, clicking, or typing

- Wrong actions might be harmful

- In a real-world scenario, the agent might not be able to undo an action (e.g. sending mails, booking flights, editing CRM entries, etc.)

Approach: Getting Some Baselines

One issue we face is that we have to align a large trajectory of agent’s actions with a natural language instruction. When using LLMs, the natural instruction can be broken down into smaller sub-instructions, eventually leading to one instruction per action. However, training an agent that acts based on a simple command requires action-language pairs. Existing work (Cheng et al. 2024) describes this task as UI grounding and uses automatically derived labels to train the agent to “describe the screen”, i.e., to provide a textual description of most screen elements. When the source code is available, such descriptions can be derived, for example, for in the case of web pages and Android applications. However, when such descriptions are not available, it is a huge engineering effort to create them.

Deriving the meaning uf UI elements by “clicking and observing” only works in some cases.

For example, an agent could click on the “MS Word” logo and observe that the application word.exe is started.

However, the agent is unlikely to learn what buttons like “bluetooth off”, “volume down”, etc. mean without hand-crafted labels.

Also, it will be extremely hard to learn what bold, changing, font, etc. means without any labels (as these buttons can

also be pressed without having any text written to observe their effect).

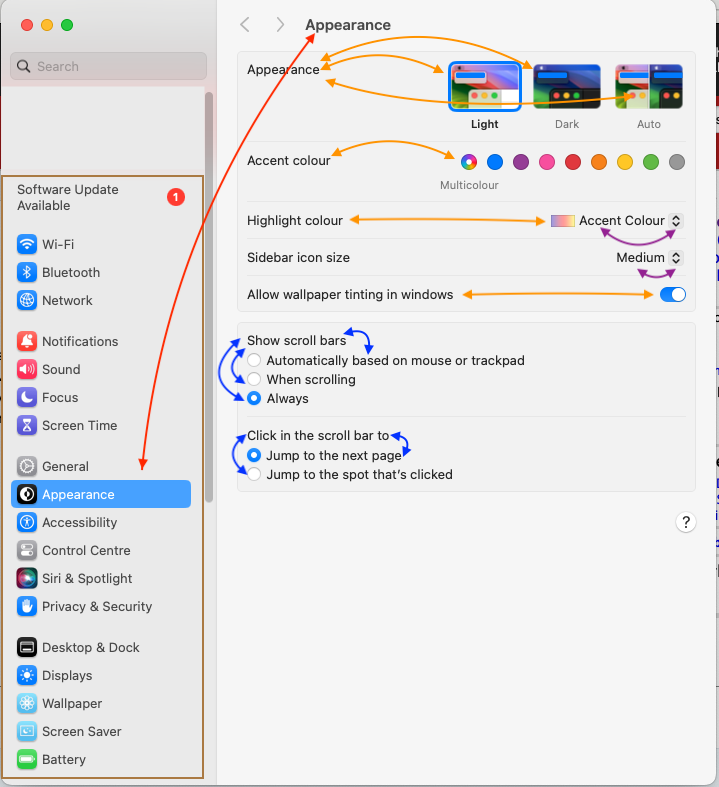

There exist no obvious solution how to create labels for UI elements of unknown applications when only the pixel UI is available. However, self-supervised pre-training on a large dataset followed by a fine-tuning on a small amount of labeled data is likely to be more sample efficient than training from scratch. During such a pre-training, common concepts of buttons, text fields, etc. can be learned. Furthermore, when looking at computer applications, it becomes obvious that UIs are highly structured. The following picture of the settings from a Mac computer illustrates this:

Humans instantly recognize the structure of the settings window as they solve the “binding problem” how the elements are related to each other. We know which text belongs to which button, which button belongs to which sub-window, etc. Learning such relations in a pre-training seems likely to help for downstream tasks. To large extend, such relations can be learned from web pages. Especially if the CSS is edited in a way to create Mac-, and Windows-like UIs, it is likely that the agent can learn the structure of the UIs for various applications. The advantage of web pages is that they exist in a vast amount and are easy to access (simple to obtain the data). Alternatively, we could build a generative model (e.g. hard-coded or learned with GANs) to generate UI descriptions following the Mac/Windows/Linux style. These descriptions can then be rendered to obtain screenshots-descriptions pairs.

Directly Predicting User Actions - I don’t believe in it

A very simple alternative approach could be to predict the next screen given the current screen and the action. Therefore, the computer runs in a virtual environment (a “gym-like” environment) and the agent can observe the screen and execute actions. By executing actions and predicting the screen change, the agent learns the consequences of actions. After pre-training, a query encoder is tuned so that the correct action is selected for a given textual instruction. A very similar approach is to observe humans interacting with computers and predict their next action.

I don’t believe in this approach as

- it is sample inefficient,

- not every action leads to UI changes (e.g., select bold without having written text),

- it requires huge amount of resources,

- etc.

Similar work has shown that vast amounts of data are required to learn from human demonstrations. For example, for simple web-tasks, most SOTA approaches use more than 25k demonstrations per task (Humphreys et al. 2022). Even though our approach could be more sample efficient, we would probably still require thousands of demonstrations per task. Since we want to control the entire computer, the number of samples required would be enormous (while probably having only a few persons allowing to observe their screen).

Also, the argument of Yann LeCun that building generative models for sensory inputs is often intractable is likely to hold here as well.

“If your goal is to train a world model for recognition or planning, using pixel-level prediction is a terrible idea. Generation happens to work for text because text is discrete with a finite number of symbols. Dealing with uncertainty in the prediction is easy in such settings. Dealing with prediction uncertainty in high-dimension continuous sensory inputs is simply intractable. That’s why generative models for sensory inputs are doomed to failure.”

– Yann LeCun

Other work (Ma, Tsao, and Shum 2022) argues that these predictions should be made in the latent space. I believe that mapping UIs to hierarchical descriptions of its element and learning actions on this level goes towards this direction: It is a much lower-dimensional space and allows to predict the consequences of actions in a more sample-efficient manner (towards the parsimony principle described by (Ma, Tsao, and Shum 2022)). Furthermore, encoding a screenshot to a hierarchical description and predicting how an action will change this description fulfills the self-consistency principle described by (Ma, Tsao, and Shum 2022). This is closely related to the homomorphic autoencoder described by (Keurti et al. 2023). Furthermore, having a hierarchical description of the UI allows to align the elements with language instructions.

Two Binding Problems

I identify two types of binding problems that have to be solved: First, the binding between UI elements. Second, the binding of pixels to UI elements.

The first binding problem is the problem of understanding how UI elements are related to each other. This problem is solved by learning a hierarchical description of the UI. When we know which button and text belong together, we can derive the meaning behind the button. This is a problem that is solved by humans instantly when looking at a UI as we have this understanding between relations. Furthermore, the observation space becomes much smaller as we move from pixel-based observations to a hierarchical description of the UI. I believe that these are the main reasons for the success of LLMs in computer control.

The second binding problem is the problem of understanding which pixel belongs to which UI element. As outlined above, SOTA approaches require huge amounts of training data, e.g. 25k demonstrations for solving simple web tasks (Humphreys et al. 2022). I believe that observing actions on pixel level is highly inefficient: There are countless ways how one can move the mouse to a button, on which pixel of the button is clicked, etc. Other datasets provide actions as textual descriptions (e.g. button “xy” is clicked). However, creating such annotations is costly. Therefore, I argue that we should not only predict hierarchical descriptions of the UI but also the bounding boxes of the UI elements. This allows to automatically convert humans actions conducted on pixel level into descriptive actions that can be linked to the hierarchical description of the UI. So far, I am not aware of any work that predicts the bounding boxes of UI elements from pixel-based observations.

Pre-Training

We could pre-train the model to map UIs to hierarchical descriptions and bounding boxes of its elements. Therefore, we can either use a web-dataset (scraped web pages) with multiple stylesheets mimicking the Mac/Windows/Linux style or build a generative model to generate UI descriptions. In both cases, we obtain screenshots-descriptions pairs. These descriptions are hierarchical, implicitly encoding the binding of elements.

We then learn to observe the screen and predict the corresponding description. Training the model could follow the principles described by (Ma, Tsao, and Shum 2022), (LeCun 2022), and (Shaw et al. 2023). Thus, with pre-training, we can obtain a model to map pixel-based UI observations to hierarchical descriptions of its elements.

I think having these two binding problems solved is fundamental for controlling computers. It allows to act on a higher-level description and is the foundation for the following chapters. However, it is questionable if this is the approach I should focus on during my PhD as I just don’t have enough resources (e.g. some models pre-trained on HTML-screenshots require more than 500 CPU days just to pre-process 7TB of web data and use 128+ high-end GPUs for training). There exist smaller models but these are limited to predict elements and their bounding boxes for web pages only. My evaluation shows that they can predict things like “text; +” for a button. However, this information is quite useless when not encoding that there is a text besides it saying “quantity” and another text above describing the product. This specific smaller model was trained using 8 A-100 GPUs.

The Agent: V1

Let’s assume we pre-trained the model to map UIs to hierarchical descriptions of its elements. We can fine-tune this model on existing RL environments. Such environments typically comprise a NL instruction, and a application to interact with. After completing the task or running out of time, the agent receives a reward signal.

Alternatively, we could combine the pre-trained model with an auxiliary LLM for action planning and reasoning. The LLM acts as the brain, telling the agent where to click and type. In this setting, the screen recognition model maps the UI to a hierarchical description of its elements, and the LLM provides a description of how to interact with the UI (e.g. click button at location (x,y)).

These baselines can be extended with various measures already done in the current literature, e.g., using external memory to store successful workflows, etc. These versions of agents do not include a lot of novelty and others (Shaw et al. 2023, Cheng et al. 2024) implemented similar approaches already. However, the pre-training differs and could improve the results.

The Agent: V2

Let’s assume we pre-trained the model to map UIs to hierarchical descriptions of its elements. We can then observe how humans are using the computer and collect long action-screenshot trajectories. By leveraging the pre-trained model, we can derive action-UI description pairs. We can then learn to predict the next screen description given one action (optionally as language instruction) and the current screen description. As soon as the agent excels in this task, we can combine actions into action sequences and predict the next screen description given a sequence of actions (as language instruction) and the current screen description. Making the action sequences longer and longer can be regarded as a form of curriculum learning.

The Agent: V3

We build a virtual environment using many basic control elements. These elements are generated randomly and follow the Mac/Windows/Linux guidelines. Then a random subset of these elements is selected and random actions are defined that have to be executed. A LLM is used to summarize the action sequences into a language instruction (pre training) and the agent is provided with the screen description and the language instruction. The agent has to solve these tasks. The better the tasks are solved, the more complex become the tasks.

When a task cannot be solved, there exist different reasons:

- First, the generated UIs are too complex. In this case, the complexity of the UIs is reduced.

- Second, the UI description is wrong. Since we generated the UI, we know how the grounding should look like. We then update the UI description model in a supervised fashion and let the agent solve the task again. Alternatively, if we are not sure if the error is due to the UI grounding, we can provide the ground-truth description of the UI and let the agent repeat the task.

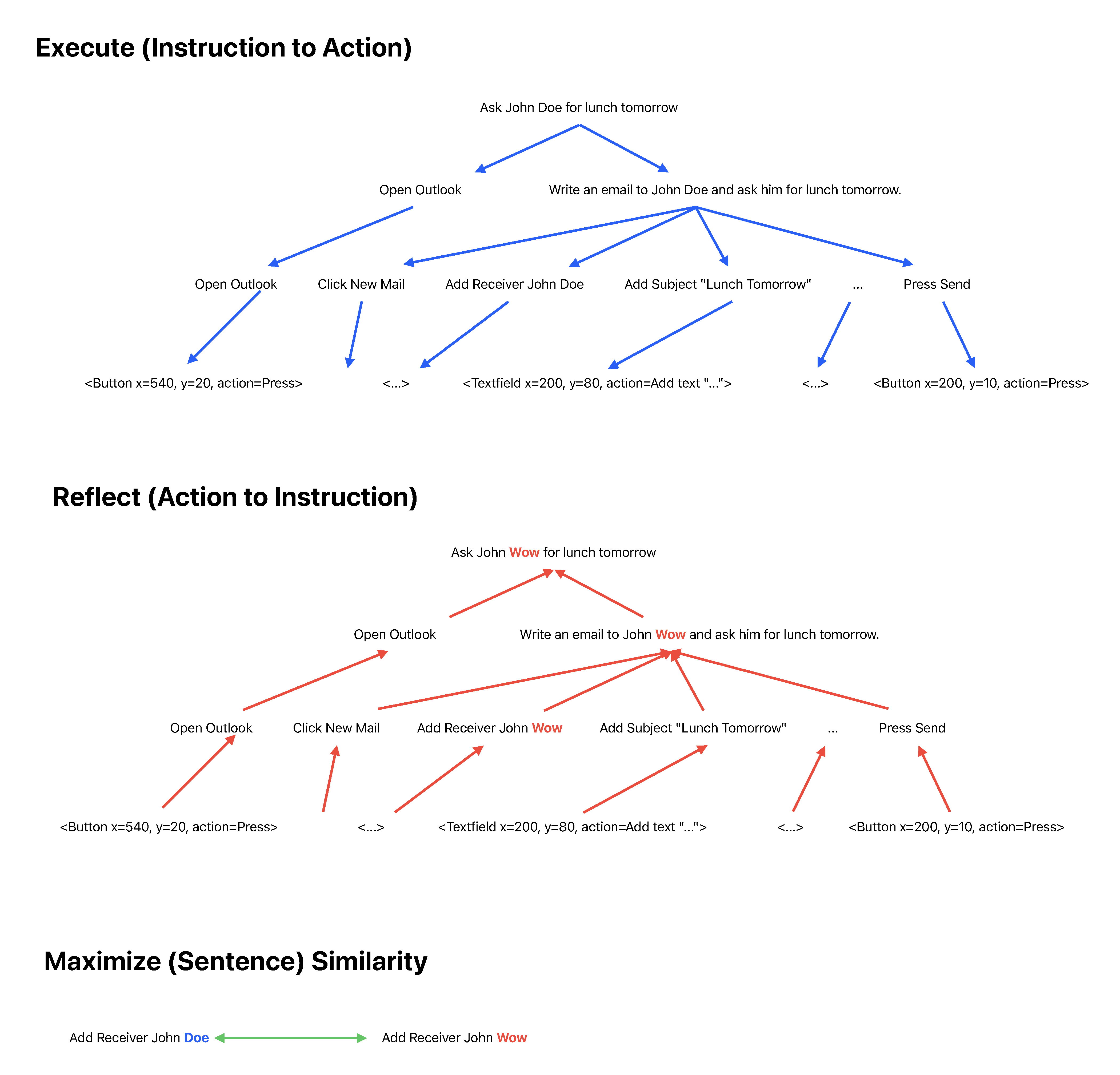

- Third, the hierarchical decomposition of the language instruction into sub-instructions or actions is wrong. Here, the challenge is that we don’t know if the automatically generated instruction is wrong or the decomposition into actions. To deal with this issue, we learn a two-way mapping, from instructions to actions and from actions to instructions. If it works properly, we should be able to encode instructions to actions and to decode actions to instructions. In this case, we follow a hierarchical update strategy as illustrated in the following:

Planning

Another angle could be to focus on the planning aspect. However, this is rather hard since 1. many researchers are working on planning action sequences for computer control and 2. the developed algorithm might not fit to the representation of the UI (e.g. we would need to train on HTML which later requires coverting all UIs to HTML).

Other Research Questions

Most of the current research is about pushing the scores on a few existing benchmarks. The knowledge is typically derived from predicting HTML from screenshots and/or interacting with a virtual environment. However, from a research viewpoint, computers provide a highly interesting environment to study intelligence.

- UI elements are easier to identify than objects in the real world: They have some uniform appearance and a high contrast to other elements, allowing to seperate them well from the background

- UIs are highly structured: They contain multiple windows, and windows contain multiple sub-windows. Each element is related to other elements (e.g., checkboxes to a text, multiple checkboxes to a description what they are doing, etc.)

Therefore, analyzing the binding problem and Gestalt phenomena seems to be easier in this environment than in the real world.

Link to Natural Intelligence and Benjamin’s group

Humans have internal models of the external world that represents all behavior-relevant information. These models are acquired by interacting with the world and are used to predict the consequences of actions. Neuroscientific findings suggest that humans, when acting, integrate efference copies of motor signals with incoming sensory observations to predict future sensory inputs (Keller et al., 2012). Hypotheses in psychology (Piaget, 1964) suggest that perceiving an object is not creating a mental copy of it but rather understanding of how this object behaves under different interventions.

Existing research in computer vision uses these insights and focuses on building actionable representations for objects within 3D worlds (Keurti et al. 2023). This work encodes images and actions to embeddings and builds consistency between transformed images in the image space and latent space. The principle is highly similar to the proposed approach: For a computer agent, we first transform the high-dimensional UI to a lower-dimensional hierarchical description and predict action consequences in this space.

Current (unpublished) work focuses on the relation between objects. Again, this is highly similar as we build these representations for UI elements using a hierarchical description of the UI.

Ignore this

- Build segmentation masks: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Document/elementFromPoint, https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Element/getBoundingClientRect

- To read: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=SyNPk2R9K7

References

- Cheng, Kanzhi, Qiushi Sun, Yougang Chu, Fangzhi Xu, Yantao Li, Jianbing Zhang, and Zhiyong Wu. 2024. “SeeClick: Harnessing GUI Grounding for Advanced Visual GUI Agents.” arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.10935.

- Humphreys, Peter C, David Raposo, Tobias Pohlen, Gregory Thornton, Rachita Chhaparia, Alistair Muldal, Josh Abramson, Petko Georgiev, Adam Santoro, and Timothy Lillicrap. 2022. “A Data-Driven Approach for Learning to Control Computers.” In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, edited by Kamalika Chaudhuri, Stefanie Jegelka, Le Song, Csaba Szepesvari, Gang Niu, and Sivan Sabato, 162:9466–82. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v162/humphreys22a.html.

- Keller, Georg B., Tobias Bonhoeffer, and Mark Hübener. 2012. “Sensorimotor Mismatch Signals in Primary Visual Cortex of the Behaving Mouse.” Neuron 74 (5): 809–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.040.

- Keurti, Hamza, Hsiao-Ru Pan, Michel Besserve, Benjamin F Grewe, and Bernhard Schölkopf. 2023. “Homomorphism AutoEncoder – Learning Group Structured Representations from Observed Transitions.” In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, 202:16190–215.

- LeCun, Yann. 2022. “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence.” Open Review 62 (June).

- Ma, Yi, Doris Tsao, and Heung-Yeung Shum. 2022. “On the Principles of Parsimony and Self-Consistency for the Emergence of Intelligence.” Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 23 (9): 1298–1323. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2200297.

- Piaget, Jean. 1964. “Cognitive Development in Children: Piaget Development and Learning.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 2 (3): 176–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660020306.

- Shaw, Peter, Mandar Joshi, James Cohan, Jonathan Berant, Panupong Pasupat, Hexiang Hu, Urvashi Khandelwal, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2023. “From Pixels to UI Actions: Learning to Follow Instructions via Graphical User Interfaces.” arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.00245.